The goal of question-answering instruction is to "aid students in learning to answer questions while reading and thus learn more from a text" (NICHD, 2000, p. 4-86). This strategy may be especially helpful for school-based learning and test taking, but when questions require higher-level thinking, adults also may apply this kind of thinking to a variety of reading tasks (Duke & Pearson, 2002).

To build higher-order thinking skills you have to ask good questions. Research suggests that if you mainly ask factual questions, readers will learn to focus mostly on facts when they read. On the other hand, if you ask questions that demand higher-level thinking and use of background knowledge in combination with textual information, they will tend to think this way when they read (Duke & Pearson, 2002). Of course, literal comprehension is vital; a reader can't make inferences and draw conclusions without control over the basic facts. Just don't stop there. Ask questions that require learners to think about their reading.

Teaching readers to make inferences. When readers make inferences they put information from different parts of the text together with their own knowledge to arrive at understandings that are not directly stated. Making inferences is sometimes called "reading between the lines."

This kind of thinking while reading doesn't come naturally to all learners, but it is important, and may be especially important for adults in basic education and literacy classes because their general knowledge in academic content areas may be limited. The less a reader knows about the subject matter of a text, the more inferences will be required. If a learner is reading a short article about the Civil War and doesn't have much background knowledge, he may have to infer (for example) that Robert E. Lee was an important leader of the southern army. This reader will have to work harder to figure out "who the players are" than another who knows more about the war.

Adult learners may not understand that readers are expected to make inferences about text. They may not realize that they should make inferences while reading as they do in listening. Explicit instruction may be required. Here is a possible sequence.

Begin by defining inference and explaining why reading between the lines is necessary for full comprehension.

Then use a scenario based on everyday life to illustrate how we all make inferences every day. You might tell this story, for instance,

"People these days stay pretty active even when they get up in years. Yesterday I stepped into the hall to put out some bills for the mailman before the holiday, and I saw my elderly neighbor walking toward the building carrying two big grocery bags. Another neighbor stepped up to help her, and as they came into the building, I overheard them talking. The older woman said, 'Would you look at all this food! And I had to buy such a big turkey! I haven't cooked one in years. I hope I remember how!'"

Then ask the learners, "What do you think is about to happen?" (The older woman is probably having company for a holiday dinner.) "Where do you think these people live?" (They probably live in an apartment building.)

Be sure to ask, "What makes you think so? What clues did you use?"

Explain that as readers we figure out things that are not directly stated by using exactly the same kind of thinking they just used in listening: We use our knowledge of the world or of the subject matter.

Model the thinking process by reading a passage to the group and thinking aloud, demonstrating how you make inferences. Be sure to point out the text clues that support your inferences. Here's an example from the Partnership for Reading booklet for parents, A Child Becomes a Reader: Birth Through Preschool.

The following is a list of some accomplishments that you can expect for your child by age 5. This list is based on research in the fields of reading, early childhood education, and child development. Remember, though, that children don't develop and learn at the same pace and in the same way. Your child may be more advanced or need more help than others in her age group. You are, of course, the best judge of your child's abilities and needs. You should take the accomplishments as guidelines and not as hard and fast rules. (Armbruster, Lehr, & Osborn, 2003, p. 25)

Here is one way to demonstrate what a parent might infer from this passage:

"It seems like the list that's coming up will tell some things that 5-year-olds can do. I guess that's what they mean by 'accomplishments that you can expect.' But it says children are all different, and I'm the best judge of my child, so I think that means I shouldn't be upset if my child can't do everything on the list."

Next ask pairs or groups to read a passage and discuss their inferences. Be sure they specify the clues (evidence) they used, and encourage them to challenge each other if the evidence seems insufficient to justify the conclusion. Observe and assist the groups if they need help finding these "invisible messages" (Campbell, 2003).

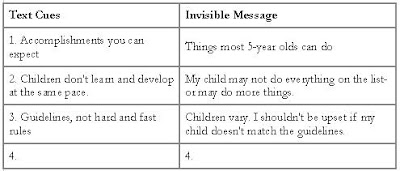

Have individuals practice with another text, and complete a table like the one below (Campbell, 2003), writing information from the text in the left column and the corresponding inference on the right.

Provide feedback on this activity and more practice as needed.

Analyzing questions. After explicitly teaching this kind of thinking, you may teach learners to analyze questions to see where and how to find the answers. You might try the question-answer relationship (QAR) approach (Raphael & McKinney; Raphael & Pearson, as cited in Duke & Pearson, 2002). Three QARs may be taught:

- Right There questions, when the answer is directly stated in the text,

- Think and Search questions, when the reader must do some searchingÑcombining information from different parts of the text, and

- On My Own questions, when the question requires the use of prior knowledge combined with text information.

Answering questions may be understood as the foundation for generating questions, the next strategy. Before you can expect readers to ask good questions of themselves, you have to give them examples of different kinds of questions (Curtis & Longo, 1999). It makes sense to first focus on questions you ask. Then, when the learners are aware of different kinds of questions and have practiced finding answers, you might try the question generating strategy, modeling as in the example on page 92.

Click on Back Arrow to Return to the Module